Skin tags: Why they develop, and how to remove them

Skin tags: Why they develop, and how to remove them

Skin tags are harmless growths that can appear anywhere on your skin, but often develop on the neck, eyelids, or underarms. They may be the same color as your skin or darker. Some are pink. Others turn red when irritated. You may see one dangling from a stalk, while another is firmly fixed to the skin.

With all this variation, there is one thing that acrochordons (medical name for skin tags) seem to have in common. Many people want to remove them.

The following explains how dermatologists remove skin tags. It also answers other questions that patients frequently ask their dermatologist.

Why am I getting skin tags?

These growths can appear anywhere on the skin, but they usually develop where skin has been rubbing against skin, jewelry, or clothing for some time. That’s why they usually occur in one or more of these areas:

-

Breasts (beneath)

-

Eyelids

-

Groin

-

Neck creases (or where clothing or jewelry rubs against the neck)

-

Underarms

Skin tags are also commonly found on the sides, abdomen, or back.

Because they develop where skin rubs against skin, people who are overweight, pregnant, or have loose skin are more likely to get skin tags.

You also have a higher risk of developing skin tags if you have diabetes, metabolic syndrome (high blood pressure, unhealthy blood sugar levels, extra fat around your waist, or unhealthy cholesterol levels), or a blood relative has skin tags.

It’s important to keep in mind that these growths are harmless.

Should I remove a skin tag?

Because they’re harmless, a skin tag only needs to be removed if it:

-

Becomes irritated or bleeds

-

Develops on your eyelid and affects your eyesight

-

Feels painful, especially when the pain comes on suddenly

A skin tag can become irritated if it frequently rubs against jewelry, clothing, or a seat belt. Shaving can also irritate it, especially if you nick the skin tag. A dermatologist can remove these skin tags.

If you dislike the way a skin tag looks, your dermatologist can also remove it. Keep in mind that insurance providers consider removing a skin growth for looks alone a cosmetic treatment. Insurance rarely covers the cost of cosmetic treatments.

How does a dermatologist remove skin tags?

Your dermatologist can quickly and safely remove one or more skin tags during an office visit, and usually without the need for a follow-up appointment.

The treatment that your dermatologist uses will depend on the size of the skin tag, where it appears on your body, and other considerations.

Your dermatologist may use:

-

Cryosurgery: During this treatment, your dermatologist applies an extremely cold substance like liquid nitrogen to freeze and destroy the skin tag. Sometimes, freezing causes a blister or scab. When the blister or scab falls off, so will the skin tag.

When using cryosurgery, your dermatologist may freeze only the bottom of the skin tag and then snip it off with a sterile surgical blade or scissors. -

-

Electrodesiccation: Your dermatologistuses a tiny needle to zap the skin tag, which destroys it.You’ll develop a scab on the treated skin that will heal in one to three weeks.

-

Snip: Your dermatologist will numb the area, use sterile surgical scissors or a blade to remove the skin tag, and then apply a solution to stop the bleeding.

After treatment, your dermatologist may give you aftercare instructions to follow. This may include removing the bandage, washing the area carefully, and covering it with a new bandage.

Follow your aftercare instructions carefully to prevent problems like an infection.

Does wart remover work on skin tags?

Given that some skin tags look like warts, it’s easy to think wart remover would work well. It doesn’t.

Warts are hard and need strong medication. Skin tags are soft, so using a wart remover on them can damage your skin. You may develop scarring or irritated skin where you apply wart remover.

Seeing a dermatologist can give you peace of mind

Skin tags come in many shapes and sizes, so you may mistake a wart or even a skin cancer for a skin tag. Board-certified dermatologists know the difference between something small and something major. By seeing a dermatologist, you’ll find out what’s going on and that can bring peace of mind.

Reference: American Academy of the Dermatological Association.

So That’s Why Your Skin Gets Crepey As You Get Older

So That’s Why Your Skin Gets Crepey As You Get Older

Crepes may be delectable, but crepey skin? Not so much.

The term describes skin that, like crepe paper, appears thin and crinkled and typically lacks the elasticity, thickness and firmness of youthful skin.

“Crepey skin is primarily an aesthetic concern but it can also be indicative of potential health issues,” board-certified dermatologist Dr. Shoshana Marmon told HuffPost. “Since it usually develops as a result of substantial sun damage, individuals with crepey skin may be at increased risk for the development of skin cancer. Additionally, since crepey skin is thinner and less elastic, it may be more susceptible to bruising and tearing, which could lead to infection if not properly cared for.”

Plenty of creams and lotions claim to alleviate the appearance of crepey skin, and anyone who wants to take care of it quickly can seek doctor-administered treatments. We spoke with experts who weighed in on what works best and whether there’s anything you can do to prevent crepey skin from forming in the first place.

Why and when crepey skin forms.

As Marmon hinted, crepey skin primarily results from sun exposure. “A frequent misunderstanding is that crepey skin develops solely from aging, but lifestyle factors like sun exposure and smoking are significant contributors,” she said. “While everyone is susceptible to crepey skin, people with lighter skin tones, who are more prone to sun damage, are particularly at risk.”

Sun exposure causes the skin to lose volume due to dehydration. “It doesn’t store water the same because the integrity of the skin is damaged,” board-certified dermatologist Dr. Shani Francis told HuffPost. That leads to degradation of collagen and elastin, the proteins that hold water and therefore help the skin keep its structure.

Any ultraviolet exposure, even from tanning beds, can lead to the formation of crepey skin. “It’s really not the sun itself — it’s ultraviolet radiation,” Francis explained. “Any type of ultraviolet radiation exposure is going to damage and degrade the collagen and the elastin tissues.”

Genetics play a factor, too. “If you look at your parents, if they have crepey skin, you know you need to start the process of preventing a little bit earlier,” Francis said.

According to Marmon, many women begin to notice crepey skin around the time they hit menopause because the drop in estrogen during that time speeds up the decrease in collagen and elastin, resulting in a thinning of the skin with a loss of moisture and fat.

“It starts around middle age and gets worse as we age,” Francis reiterated. “The elastic fibers, they start off very strong. Twenty-something-, 30-something-year-olds, their skin snaps right back. Once you get to 40, it doesn’t quite work that way.”

Board-certified dermatologist Dr. Noëlle S. Sherber told HuffPost that crepey skin from UV damage usually shows up around the eyes, the chest and the backs of the hands. Some people also see it above the knees and on the inner arms.

What you can do to prevent crepey skin.

Wearing sunscreen may seem like the obvious way to ward off crepey skin, but Francis said another method may be more effective.

“You can’t see light through your clothes — that’s better,” she said, “Sunglasses, a hat, those things are always better than sunscreen because they’re on and in place. Sunscreen doesn’t last. It’s not permanent. Sun protection instead of sunscreen is much more comprehensive. I always tell people, think of sunscreen as your last line of defense.”

For the areas that clothing and accessories can’t cover, apply sunscreen. The American Academy of Dermatology recommends a water-resistant one that offers broad-spectrum protection with SPF 30 or higher.

Some over-the-counter options to try for crepey skin.

Marmon wants to temper expectations of seeing results from over-the-counter treatments claiming to eliminate the appearance of crepey skin. “While creams, moisturizers, lotions and especially sunscreen are helpful in maintaining skin health, eliminating all signs of aging is pretty much impossible,” she said.

However, with regular use, topical products with ingredients such as retinoids, alpha hydroxy acids, peptides, growth factors, hyaluronic acid and antioxidants can help to stimulate collagen production, therefore improving skin quality.

“These products generally take several months before you see their potential benefit,” Sherber warned, adding that a high price tag doesn’t equate to a higher likelihood for results. “A misconception is that only high-end skin care products can combat crepey skin, when in fact, consistent use is far more important than the price tag.”

You want to make sure the moisturizer you pick also contains water to rehydrate the skin. “Water is the number one hydrator,” Francis said. “A big mistake people make is coating skin with oil when they’re already dehydrated because all that’s going to do is improve the barrier.”

Francis particularly loves products with niacinamide, a form of vitamin B3, as a way to help alleviate the appearance of crepey skin. It can also be taken as a supplement.

Sherber offered an easy way to test whether a moisturizer is thick enough to properly hydrate: “When you open the jar and flip it upside down, if it doesn’t drip, then it should be a good barrier support product.”

Doctor-administered treatments to address crepey skin.

On May 15, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first skin booster, Skinvive by Juvederm, to improve skin smoothness in adults over 21. The booster is an injectable hyaluronic acid with a serum texture that has been used for years overseas, where they refer to it as Volite. “Unlike fillers, which volumize, skin boosters replenish skin’s deep hydration and can give fantastic results for skin quality improvement, especially in thin-skinned areas that are prone to crepey texture,” Sherber explained.

Other injectables, like Radiesse and Sculptra, stimulate the body to synthesize collagen. Options such as radio frequency skin tightening and fractional non-ablative lasers stimulate the body’s natural healing process, leading to the production of new collagen and elastin that promotes thicker and more elastic skin. “Both can significantly improve skin quality,” Sherber said.

For certain anatomical areas, such as around the eyes, she suggested neuromodulators like Botox for reducing crinkling.

Still, “while we can somewhat improve the appearance of crepey skin, the aging process is ongoing and inevitable,” Marmon said. “It is important to have realistic expectations in terms of what to expect from anti-aging products regardless of what they claim to do. Aging is a natural part of life and much better than the alternative.”

Looking to boost the youthful appearance of the skin on your body? Try one of these skin care products for your body that include retinol.

Reference: Huffpost: By Dana Rose Falcone: Updated June 18, 2024

Teeth stain removal and whitening solutions

Teeth stain removal and whitening solutions

Is teeth stain removal on your mind? Superficial or extrinsic stains are on the outside of the teeth and can be caused by food, dark drinks, or tobacco. Read on to find out more on how to remove teeth stains.

You can prevent new teeth stains by avoiding foods and drinks that stain teeth or by brushing your teeth immediately after eating them.

Your toothbrush removes teeth stains by the mechanical action of the bristles against the tooth surface. Additionally, using a whitening toothpaste can help the process of teeth stain removal as it contains granular silica particles that polish the enamel to expose cleaner and whiter enamel underneath.

Teeth stain removal tips

Teeth stain removal can be achieved by several teeth whitening procedures:

-

Professional teeth whitening at your dentist’s office

-

The regular use of whitening toothpaste

Why Coffee Stained Teeth Happen

Coffee may get you going in the morning, but it won’t make your teeth whiter. Coffee stained teeth occur over time, and these stains can make you self-conscious.

Coffee stained teeth occur when tannins in the coffee build up on tooth enamel. Good oral hygiene can help reduce coffee stained teeth, but that isn’t always enough. Some whitening toothpaste can remove up to 90% of stains on the tooth surface after 14 days. But sometimes you need something stronger to remove coffee stains from teeth.

Solutions for Coffee Stained Teeth

You don’t need to live with coffee stained teeth. Please see below options to improve the appearance of coffee stained teeth:

-

Dramatic Whitening: Oral-B 3D White Luxe toothpaste can help improve coffee stained teeth and provides noticeable whitening results after seven days of use.

-

-

Gentle Whitening: If you have teeth sensitive to whitening, Oral-B 3D White Delicate White can help improve the appearance of coffee stained teeth gradually.

-

-

Ongoing Whitening: Oral-B 3D White Luxe Anti-tobacco toothpaste is designed to remove stains caused by food, beverages, and tobacco.

- {/youtube}v=Brtf1lQ7Qp4{/youtube}

-

Help prevent a recurrence of coffee stained teeth. Keep a toothbrush and toothpaste at work for use after you have had your morning coffee. Not convenient? Even rinsing your mouth with water after drinking coffee can help prevent coffee stains on teeth and maintain your whiter, brighter teeth.

Reference: Oral B Tips

Eye Infection from False Eyelashes

-

Bacterial infections: These are the most common cause.

-

Skin conditions such as eczema, dandruff, and psoriasis can trigger eyelid inflammation (blepharitis), which can lead to infection if left untreated.

-

Anterior blepharitis affects the outside of the eye, along the outer lash line.

-

Posterior blepharitis affects the inner part of the eyelid that borders the eyeball.

-

Blepharitis

Blepharitis is a common eye condition that causes the eyelids to become sore and inflamed

What is blepharitis?

Blepharitis causes eyelids to become red, swollen and inflamed. It doesn’t normally cause serious damage to the eyes, but it can be very uncomfortable. It tends to be a long-term condition, which means you’re likely to need ongoing treatment. Severe cases do have a risk of causing long-term damage, but fortunately these are quite rare.

Types of blepharitis

There are two main types of blepharitis – anterior and posterior.

Anterior blepharitis

When the front (anterior) part of the eyelids becomes sore, this can be caused by an infection, allergy or a general sensitivity to bacteria present on the eyelids. It can also be associated with some scalp conditions, such as very dry or oily skin and dandruff.

Posterior blepharitis

Also known as meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) is when the glands that make the oily part of your tears become blocked. Both types of blepharitis can cause dry eye or make it worse if you already have it. Many people will have a combination of blepharitis, meibomian gland dysfunction and dry eye.

Risk factors

Blepharitis is more common in people over the age of 50, but anyone can develop it. This is often because the glands that make the normal tears, particularly the oily part of the tears, tend to become less effective as you get older.

Symptoms

Blepharitis can cause crusting and white scales may stick to the roots of eyelashes. Your eyelid edges may become red and your eyes will feel gritty, burning, sore or itchy. If you experience these symptoms, make an appointment with your optometrist.

Treatment

There is a range of products designed especially for treating blepharitis, such as sterile pads, individual moist wipes and separate cleaning solutions.

Your optometrist will be able to advise you on where you can buy these products. Antibiotic ointment may be recommended in severe cases.

As part of the treatment, you need to remove all the crusting and debris from the edge of your eyelids and from between your eyelashes. You should use your cleaning product. If this is not available, you should use warm water and cotton balls or make-up removal pads. Treatment of blepharitis is a long-term procedure. You may not see any improvement for several weeks.

Continue the treatment twice a day for at least one month, then less often as it starts to get better. You will probably need to continue to clean your lids at least twice a week to help prevent the blepharitis from returning.

Blepharitis treatment method

- Wash your hands before and after cleaning your eyelids

- Rub the moistened pad or cotton ball firmly but gently along the eyelid edges to remove the crusts and debris

- Take care to wipe between the eyelashes of both the upper and lower lids

- Use a fresh pad or wipe each time

- Dry your eyes gently.

Resources for your practice

You can download our patient leaflet on blepharitis.

If you're a practitioner, we recommend that you use this information, following a suitable examination, to reinforce advice given to the patient who has symptoms of blepharitis.

For more information on eye health go to our For patients section.

Benefits of collagen for skin

Benefits of collagen for skin

Collagen, a crucial protein that serves as a building block for the skin, plays a pivotal role in maintaining its strength, elasticity and overall health. Here are some key benefits of collagen for skin:

1. Enhances skin elasticity

Collagen provides structural support to the skin, contributing to its elasticity (aka skin turgor).

As we age, collagen production decreases, leading to sagging and wrinkles. Supplementing with collagen can help restore elasticity and firmness, reducing the appearance of fine lines.

2. Promotes hydration

Collagen is essential for maintaining the skin’s moisture levels. It helps create a barrier that prevents water loss, ensuring the skin remains adequately hydrated.

Well-hydrated skin appears plump, youthful and vibrant.

Risks and side effects

While collagen is generally considered safe for most people when used in skin care or obtained from natural food sources, there are potential risks and side effects associated with certain forms of collagen supplementation. It’s important to be aware of these factors, especially if you are considering collagen supplements.

Here are some potential risks and side effects to keep in mind when using collagen for skin:

- Allergic Reactions: Some individuals may be allergic to collagen or specific sources of collagen, such as marine or bovine collagen. Allergic reactions can manifest as skin rashes, itching, swelling or difficulty breathing.

- Digestive Issues: Collagen supplements, especially in high doses, may cause digestive discomfort for some individuals. This can include symptoms such as bloating, constipation or diarrhea.

- Interactions with Medications: Collagen supplements may interact with certain medications. If you are taking medications or have underlying health conditions, consult with a healthcare professional before adding collagen supplements to your routine. There is limited evidence to suggest that collagen supplements may influence blood clotting. Individuals taking blood-thinning medications or with bleeding disorders should exercise caution and consult their healthcare providers.

Before incorporating collagen supplements into your routine, it’s advisable to consult with a healthcare professional, especially if you have existing health conditions or concerns.

Additionally, patch-test topical collagen products before widespread use to ensure they are well-tolerated by your skin.

Individual responses to collagen supplementation can vary, so it’s crucial to prioritize your health and safety.

Frequently asked questions

How does collagen help your skin?

Collagen is a protein that provides structure, elasticity and hydration to your skin.

As we age, our bodies produce less collagen, leading to thinner skin, wrinkles and sagging. By helping retain moisture and strengthen skin layers, collagen helps your skin appear firm, smooth and youthful.

What type of collagen is best for skin?

Type I collagen is most effective for skin health, as it is the primary collagen found in skin, hair and nails. Type III collagen, which often works alongside type I, also plays a role in maintaining skin’s firmness and elasticity.

Many collagen supplements contain both types I and III for optimal skin benefits. And truthfully, collagen types I, II, III, IV, V, VII, VIII, X, XII and XXII all can benefit skin.

Will taking collagen tighten skin?

Taking collagen supplements can help improve skin elasticity and hydration, which may contribute to a firmer appearance.

Although collagen alone won’t fully “tighten” loose skin, studies have shown that it can reduce the appearance of wrinkles and improve skin elasticity over time, especially when combined with a healthy lifestyle.

Can you rebuild collagen in your skin?

Yes, you can support collagen rebuilding through a healthy diet rich in vitamins C and E, which are crucial for collagen synthesis.

Additionally, retinoids, antioxidants and peptides in skin care products, along with practices like regular exercise, hydration and protection from UV exposure, can help stimulate collagen production in the skin.

Final thoughts

- There are many benefits of collagen for skin. For instance, it can help enhance elasticity, promote hydration, reduce wrinkles and fine lines, aid wound healing, boost skin texture and tone, protect against UV damage, minimize cellulite and stretch marks, improve skin barrier function, and combat inflammation.

- To boost collagen production, eat more collagen-rich foods or add supplements to your wellness routine. You can also use topical collagen for skin, along with make face masks.

- It’s also important to stay hydrated and eat a balanced diet that limits collagen-destroying foods.

- Collagen for skin use is typically safe for most adults, but it’s important to note side effects could include allergic reactions, digestive issues and interactions with medications, such as blood-thinning medicines.

- Reference: Dr AXE

Articles-Latest

- Skin tags: Why they develop, and how to remove them

- So That’s Why Your Skin Gets Crepey As You Get Older

- Eye Infection from False Eyelashes

- Teeth stain removal and whitening solutions

- Benefits of collagen for skin

- Why vitamin E should be part of your skincare regime

- Can gray hair be reversed?

- Hair loss affects 1 in 10 women before the menopause – here’s how to treat it

- Conscious ageing and Black skin: What happens when Black does crack?

- Your skin color may affect how well a medication works for you — but the research is way behind

- The C word Cancer

- Astringents

- How does light therapy work? The science behind the popular skincare treatment

- The Most Offensive Fashion Police Criticisms of All Time

- Everything you need to know about lip filler migration, as told by the experts

- Pig semen and menstrual blood – how our ancestors perfected the art of seduction

- Everything you need to know about benzoyl peroxide

- We've bleached, relaxed, and damaged our hair to make ourselves look more white

- Will this be the year that facial filler is cancelled?

- Shock of the old: 10 painful and poisonous beauty treatments

Cosmetic ingredients

LOGIN

Who's On Line

We have 85 guests and no members online

Articles-Most Read

- Home

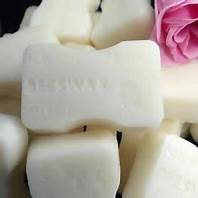

- White Bees Wax

- Leucidal

- Cosmetic Preservatives A-Z

- Caprylyl Glycol

- Cosmetics Unmasked - How Safe Are Colorants?

- Cosmetics Unmasked - Choosing Ingredients

- Cosmetics Unmasked - Colorants And Fragrances

- EcoSilk

- Toxic Beauty - Who's Looking At Cosmetics?

- Cosmetics Unmasked - Fragrances

- Microbes and Cosmetics

- Chemicals Lingering In The Environment

- Microbes and Safety Standards

- Yellow Bees Wax

- Potassium Sorbate

- Toxic Beauty - Hazardous To Your Health

- What's Happening in the USA - Cosmetic Regulations - Toxic Beauty

- Synthetics In Cosmetics - The Industry Fights Back

- Fresh Goat's Milk Soap

- Active Ingredients

- Cosmetics Unmasked - Listing Cosmetics

- Toxic Beauty - Cocktails and Low Doses

- Natural Waxes A-Z

- Natural Butters A-Z